Apparently, it’s been around for a considerable length of time; by the mid-nineteenth century, cookery books were at that point calling it “an amazing early English dish.” Along with ‘Bubble and Squeak’ and ‘Angels on Horseback’ it catches that feeling of fun-loving capriciousness related with British food that we’ve all come to adore. Without a doubt, the honest referentiality of the name – “Toad in the Hole” – brings out that syrupy Dickensian sentimentality for past times worth remembering, when kids still played together in the greenery enclosure and before our creative impulses were smothered by the reality.

Going back to the eighteenth century, it is broadly expected that Toad in the Hole was made as an approach to extend meat in poor family units. Meat was costly and families were extensive, so what little could be scratched together must be built out with less expensive ingredients. The Yorkshire pudding had been created before that century and batter-based dishes were a prominent method for filling the family requiring little to no effort. A few formulas recommend distinctive meats which can be utilized to make Toad-in-the-Hole, including beef, kidneys and lamb. In spite of the fact that the dish is referenced in different other cookery books in a similar period, the main reference to its name is in 1900, in a production called Notes and Queries that alludes to a “batter pudding with an opening in the centre containing meat”. A long way from prevalent thinking, there is no record of the dish consistently being prepared with toad substituting the meat. The reference to toad is accepted to allude the closeness in appearance to frogs lying in hold up of prey in their tunnels, their heads noticeable against the earth. It is absolutely an impossible to miss name for a dish, not least since frogs are viewed as upsetting animals and not in the least something that would whet the hunger. Maybe the notice of toads was a joking remark that for reasons unknown stuck. There is a story which may clarify the beginning of the name, however there is nothing to tell this is in excess of a nearby legend. Some state that Toad-in-the-Hole begins from the town of Alnmouth in Northumberland, where the nearby fairway was overwhelmed with Natterjack frogs. Amid a golf competition, a golfer putted his ball just for it to jump pull out before a furious amphibian raised its head, peering out of the gap that it had been resting in. The culinary expert at the inn the golfers were remaining in formulated a dish to take after this comical minute, preparing sausages in batter to seem like toads jabbing their heads out of the golf openings – and therefore Toad-in-the-Hole was conceived!

Be that as it may, toad in the hole was not generally the cherished convention it is today. The term is credited to the English curator and etymologist Francis Grose, who included it in his Provincial Glossary, an indiscriminate accumulation of overlooked axioms and words gathered around country England. Incorporated into that glossary is an overlooked Norfolk dish called “Pudding Pye Doll,” which Grose characterizes as “the dish called toad in-a-hole, or meat boiled in a crust.” Remarkably, the first occasion when that toad in-a-hole is recognized in print, Grose assumes its collectible, pre-scholarly presence.

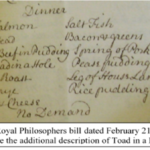

The dish originally showed up in 1769, and for the following ten years, the Royal Philosophers appreciated toad in a hole on more than one occasion per year or something like that.  At the Mitre Tavern, the eating club’s picked feasting scene, toad in the hole was served nearby such treats as venison, fresh salmon, turbot, and asparagus. Sometimes the dish springs up in winter, now and again in spring; toad in the hole was neither season explicit nor related with a specific occasion. On a few events Mr. Colebrooke felt constrained to incorporate an extra portrayal like “alias beef baked in a pudding” in the club’s dinner books, in case there ought to be any disarray among successors. Clearly, the term was not yet commonplace to everybody.

At the Mitre Tavern, the eating club’s picked feasting scene, toad in the hole was served nearby such treats as venison, fresh salmon, turbot, and asparagus. Sometimes the dish springs up in winter, now and again in spring; toad in the hole was neither season explicit nor related with a specific occasion. On a few events Mr. Colebrooke felt constrained to incorporate an extra portrayal like “alias beef baked in a pudding” in the club’s dinner books, in case there ought to be any disarray among successors. Clearly, the term was not yet commonplace to everybody.

Obviously, it is incredibly far-fetched that Englishmen hadn’t delighted in different cuts of meat baked in batter some time before the 1760s; the thought is absolutely smart, yet it’s not actually advanced science. In any case,  the entertaining name – regardless of whether it didn’t depict a totally novel dish – was significant, for it drew the dish into a rising culinary ordinance with which Britons could all things considered recognize.

the entertaining name – regardless of whether it didn’t depict a totally novel dish – was significant, for it drew the dish into a rising culinary ordinance with which Britons could all things considered recognize.

Oh dear, not every person valued the lexicographical caprice of toad in a hole. I’ve figured out how to discover a print reference from as far back as 1762, which considers toad in a hole a “slang” name for a “small piece of beef baked in a large pudding.” In George Alexander Stevens’ prominent sarcastic monologue, A Lecture on Heads (1764), Toad in a hole is as far as anyone knows “bak’d for the Satan dinner.”

It may be consequently that the proper and enlightened individuals from the Thursday’s Club deserted the dish when they migrated from the Mitre Tavern to the bigger and better prepared Crown and Anchor on the Strand in 1780. The Crown and Anchor took into account men of their word’s clubs, amenable families, and political social orders. Suppers there didn’t come modest. Be that as it may, the nonattendance of toad in a hole at this better, progressively upscale foundation may give new knowledge into the social legislative issues of English food. At the point when toad in-a-hole previously went ahead the culinary scene as a potential model of quintessential British cookery, it was upbraided as profane, unpatriotic and wicked – an attack against custom. Just as the dish in like manner sled down the social scale did it start to direction regard as a major aspect of the working man’s eating routine. When bridled to nineteenth century “industrial” values –, for example, frugality, flexibility, and time-the board – toad in-a hole was reawakened as the peculiar yet exquisite convention that still is today.